DEB COVELL ‘True’

https://www.debcovell.com

Post Minimalist Painting

Expanded abstract painting

Deb Covell ‘TRUE’

Deb Covell is a contemporary British painter working out of the traditions of abstract and minimalist painting. Her work is concerned with pure colour and paint as ‘object’ and includes large unsupported paint ‘skins’ and free flowing, unmodulated panels of various paint mediums in a limited palette heavily reliant on process and materials as opposed to representational image. It is bold and beautiful and thematically embraces the canons of art history but also enlarges the deep spiritual connexions which have fed the abstract and post-minimalist movements over the past century. Her virtual exhibition ‘True’ runs in parallel with John Stephen’s real-word exhibition ‘Pure’ in the ATELIER MELUSINE, SW France.

There is a preface and glossary on minimalist, post-minimalist, abstract painting to accompany this text. Please follow the link to read further: https://www.atelierdemelusine.com/introduction-to-minimalist-and-abstract-painting-stephens

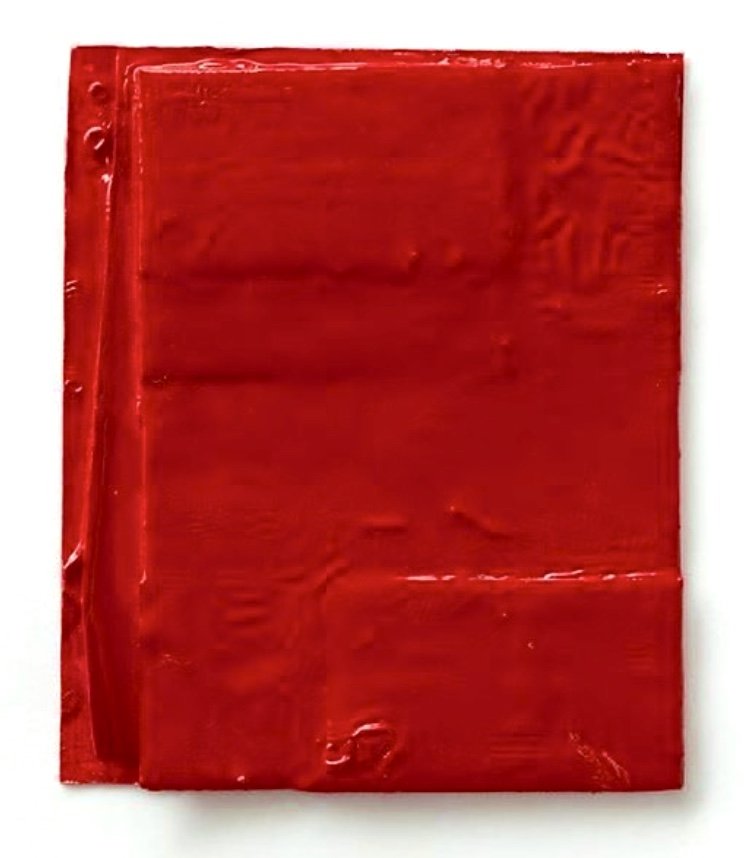

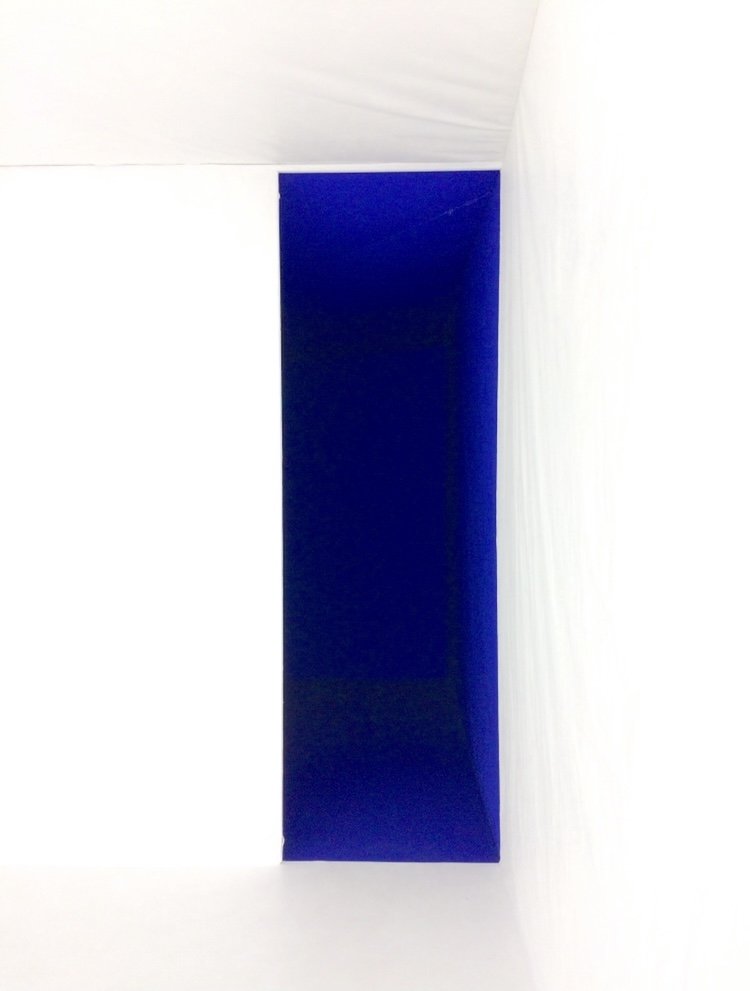

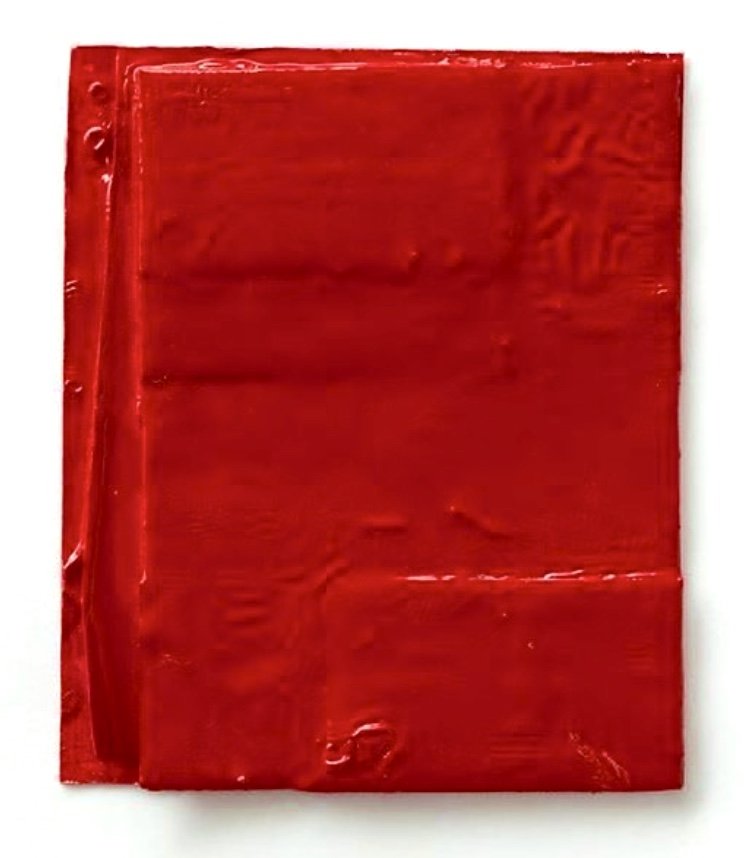

Covell from the ‘Reds’ series

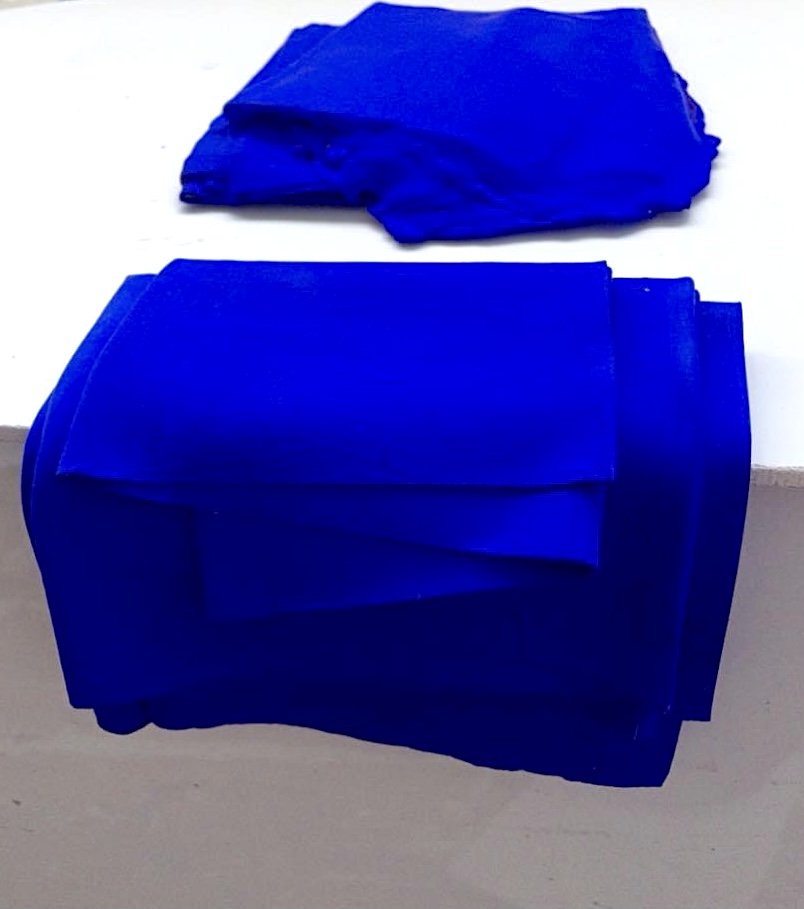

Slabs and Skins

Clean Language

Physically – what is it like?

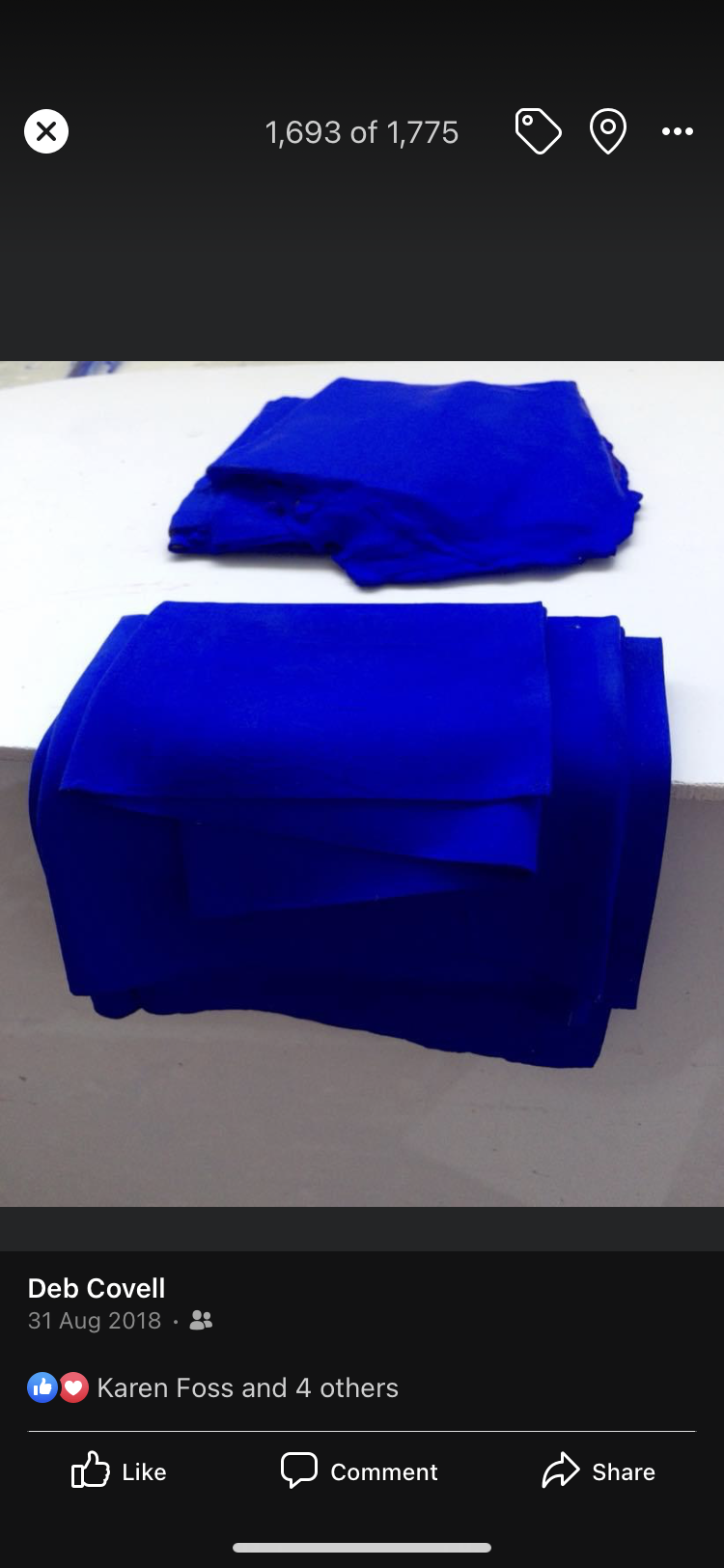

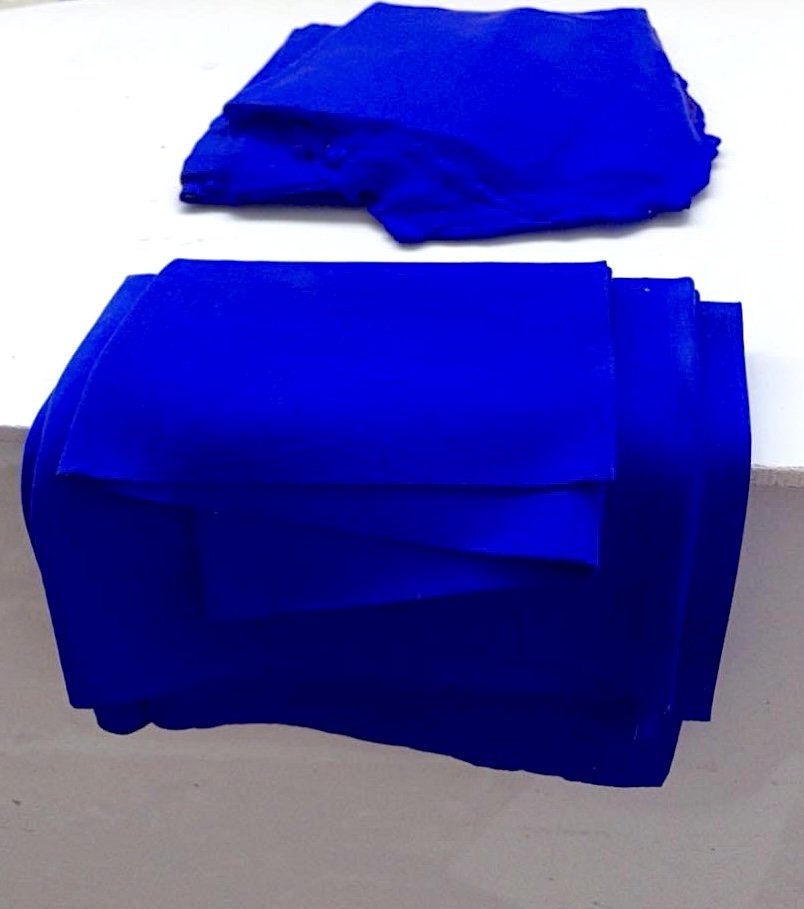

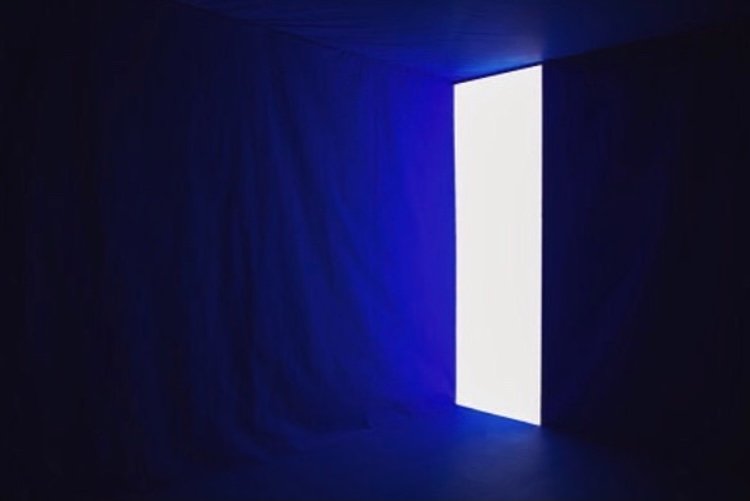

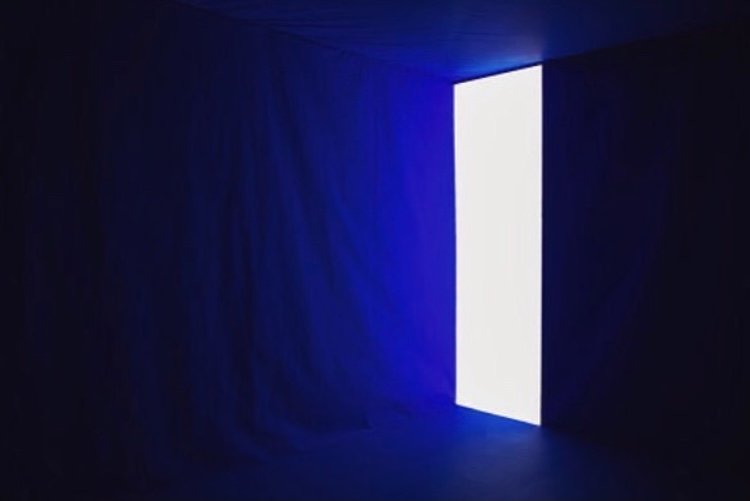

Glossy folds of lush red synthetic plastic, oil or enamel skin, insides out, contained dripping folds and compresses. Vivid blues, brilliant reds. Shocking or enveloping; colours. Draped argent sheets, suspended flags, unflapping, sticky, heavy, static. A mellow cavern of Yves Klein blue accessed from a brilliant white anti-chamber; a sensory experience inexplicably overwhelming in its simplicity. White sheets, in a white room, gently lit with white light

Bold primary's; red, yellow and deep blue. Subtle whites, strong black paint planks, poured, brushed, abandoned to dry, incised, stuck, layered repeatedly, skin upon skin. Sprawling, pleating, folding, smoothing, pressing, dragging. Changes in scale, slicing through thin plastic panels, paired down, glued down. Colour woven as fibre. The love of the paint, the edible gorgeousness of the paint. The colour. Very present and utterly soundless.

The final object reflecting the meditative repetition of the practice as well as a knowledge and absorption of the traditions of painting and esoteric colour theories.

It feels honest, weighty and true to itself. The artist is using the media of paint as itself. Almost as a single unit of colour, rather than a selection of marks creating the illusion of three dimensions on flat surface. Covell wishes to avoid the illusion of depth on a flat surface yet uses the flat surface to create depth. The paint itself becomes sculptural. Surface and image are one, without canvas or wooden support. There is no detail, you are offered pure colour which invites you more to touch it than to look at it. It becomes companion rather than vista. Covell uses primary colours, red, yellow, blue as well as black, white and metallic paints. In most cases the surface is completely un-modulated, even when folded as a skin or bundle, it remains smooth and glossy.

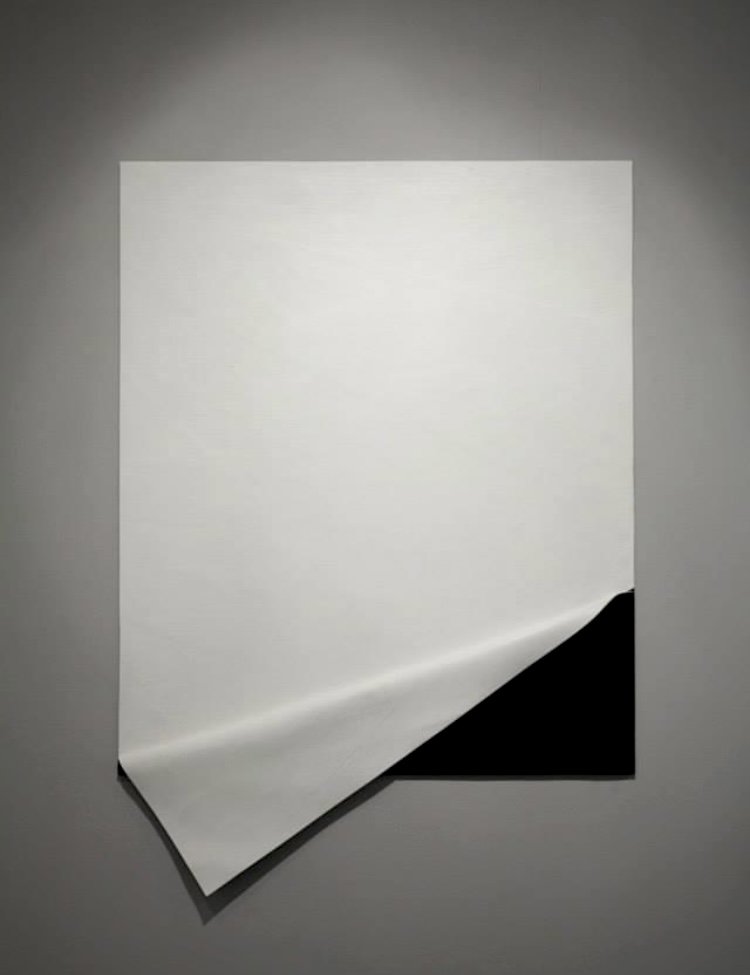

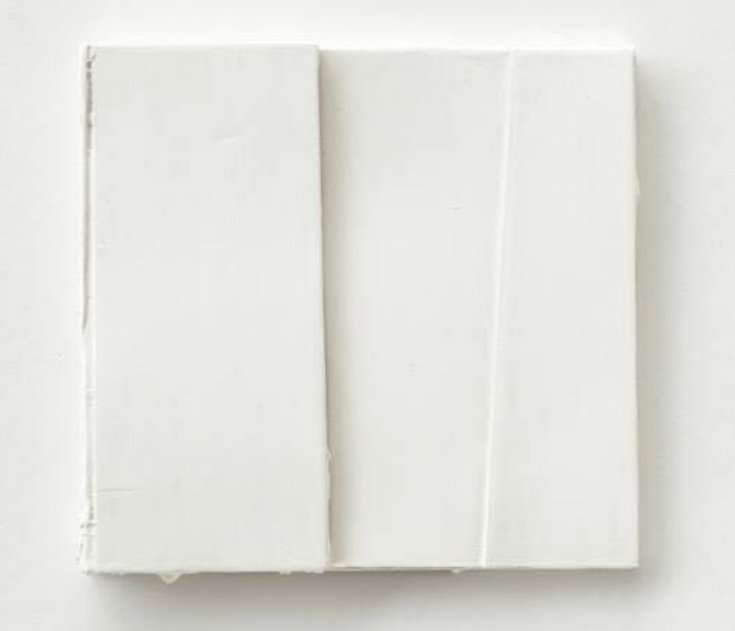

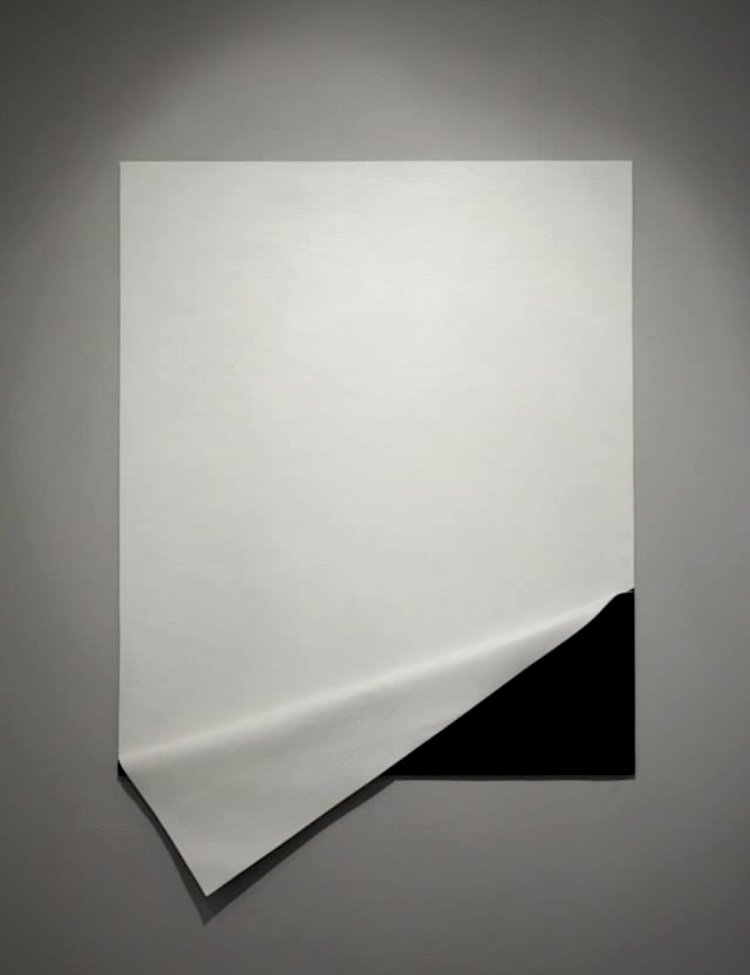

Covell from the ‘White Paint Sheets’ series

There is a clarity to the work, it is exactly what it is, coloured, dried paint. It could be compared to the technique of using ‘clean language’ which takes out all leading or influencing words, for example if a person is upset by something instead of asking “how do you feel?” and therefore attaching an emotional cue and subsequent emotional response one might ask “what is it like?”. This allows the individual to find a response less structured by the question asked (or object viewed).

When form is suggested or represented in Covell’s work it is often formed by the structure of the paint rather than a pattern or design; it is a flag, it is a fold, it is a sheet.

In particular series, such as the ‘Stations of the Cross’, with its black and white panels, we are led by the title and left to ponder and imagine the wider context and narrative, based on our own personal knowledge of the title/subject. The lexical title takes on meaning and is relational to the object, the work becomes a non-verbal metaphor which should trigger a feeling, then an emotion and a cascade of thoughts, memories and more feelings about the subject.

The connection between object and subject, metaphor and language (symbol) are foundational to humanity.

Like Stephens, Covell works with reliefs, her white series which are (unusually) rendered on supports, push forward different planes of surface in a more formal manner. In other pieces such as ‘Folds’ she collages and inverts layers of monochrome paint skins together, forming thick, two-sided pieces which are then draped, folded or peeled back and half separated into a particular position.

The Flags too are formally positioned and here some political and topical themes emerge, the flag for the Ukraine referencing the current atrocities there. This atypical use of directly referenced meaning echoes some of the masterful works of Brendan Lyons, who also uses paint as the primary descriptive medium rather than the vehicle to illustrate. His installations are comprised of trompe l’oile objects, which at first glance appear to be the real industrial object, such as a staple, a carrier bag, or hazard tape, but are in fact entirely made from sculpted paint.

With both artists the skins of paint are built up, embodying the post – minimalist methodology of applying paint in a mechanical way, painting layer upon layer to create, ‘sheets’, which can then be sculpted into objects and environs. Some, like Covell’s ‘Altered States’, big enough to walk and sit inside; from folding paint or indeed colour to being enfolded in it.

Covell a still from the ‘Altered States’ Installation

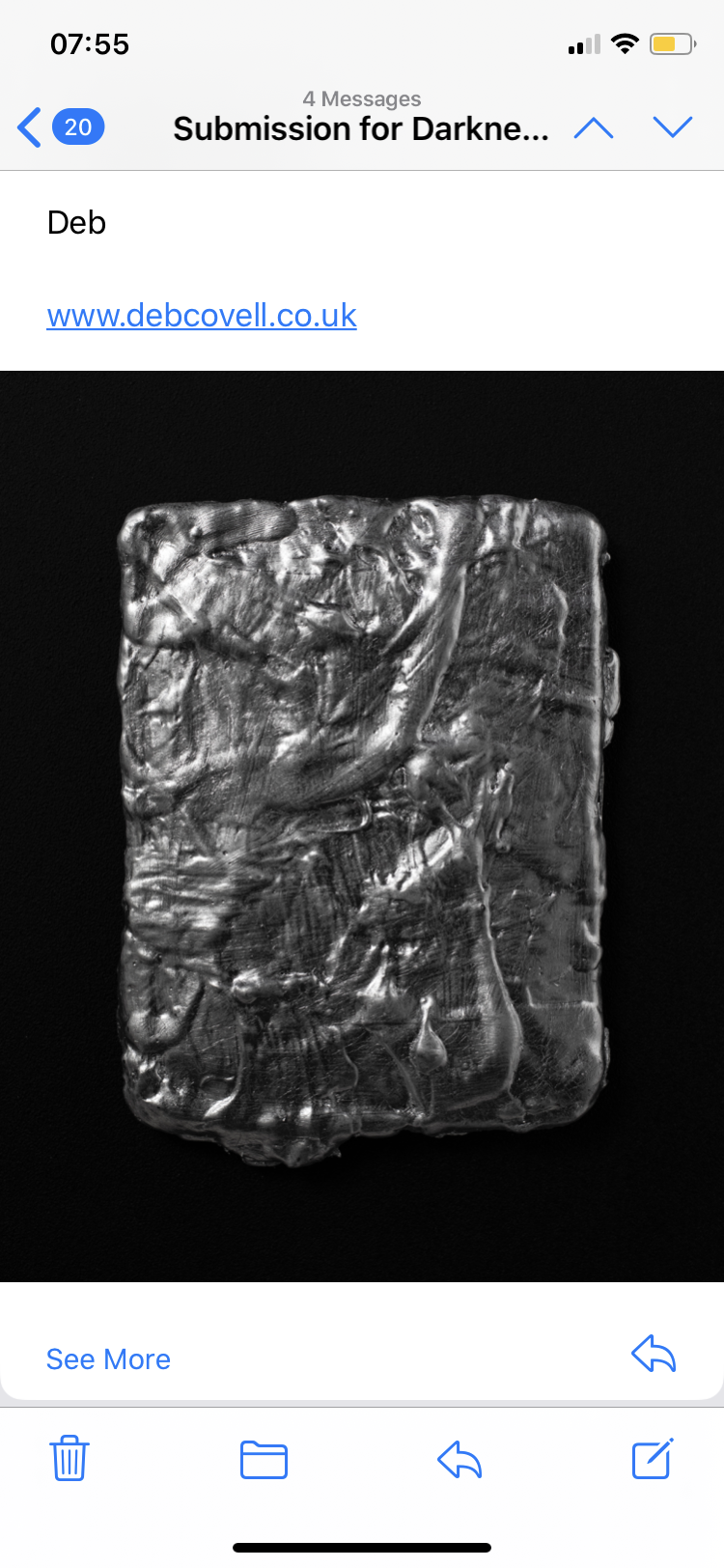

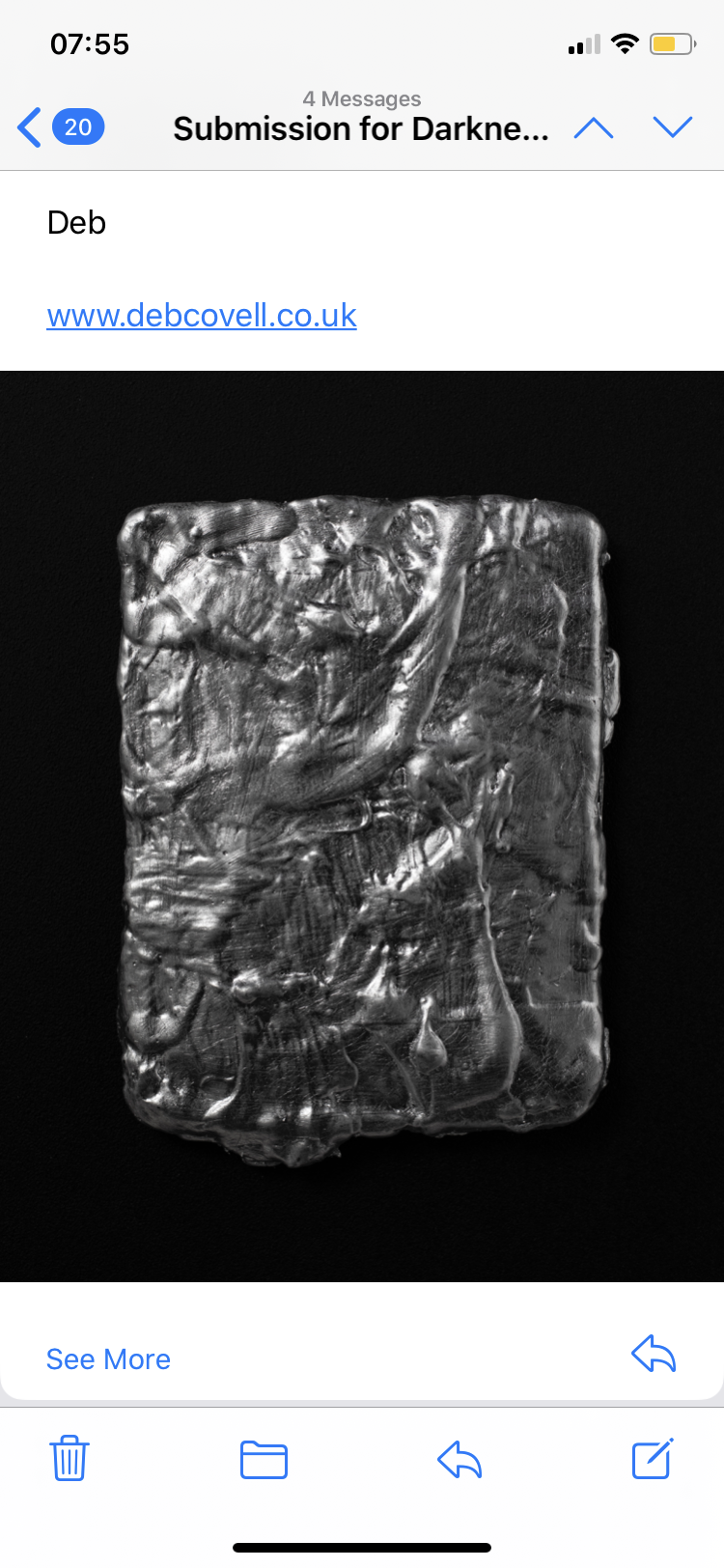

The recto-verso inside-out motif is clear, and as McHiggens suggests the location of the object and how it is lit, crucial. Like Rothko’s, Covell’s large pieces create sacred spaces. Like Lyons, Covell moves away from the limited palette of primary colours she uses, to work with metallic paints, playing with the (viewers) expectations of materials and visual sensibilities but again, using paint in an illusory manner. Soft folds of sliver or compressed sheets of what looks like soft molten metal, appear in both their practices, (which have been almost completely uninformed by each other) as does the use of the colour red. Such a powerful and iconic metaphor. Painting has very much expanded past its two-dimensional narrative usage into a subliminal and in some sense deceptive object.

I try to imagine how they smell.

Brendan Lyons ‘Red on Copper’

Background

The tradition of minimalist abstract painters which emerges in the 20C is propelled from back drop if radical social change, political upheaval and holocaust. These painters have been overwhelmingly historicised as male but more recently art historians and critics have begun to fully acknowledge the importance of female artists working in this field.

Writing about the North American protagonists of this movement, Henry writes;

(1 )“Abstract Expressionism was spoken of often in terms of military images, sports images, which is the way that everything is spoken of in American culture now. It was a very masculine language. Talking about muscularity, aggression, fighting and struggle. The joke was that every woman should find a good man and get to work under him and work her way up.”

He adds, “The women artists who were coming to prominence were gaining recognition not so much as artists but more so as fellow travellers of the guys—as their wives—like Elaine de Kooning and Lee Krasner. Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler were somewhat different, but they were still very much attached to the masculine world. (Henry. 2018.)

Deb Covell is one of a line of international women painters now working and achieving public recognition within this genre of work. Celebrated names include Kazemir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, Frank Stella, Agnes Martin (although she considered herself an abstract expressionist), Robert Ryman, Ellsworth Kelly, Anne Truitt, Sol Le Witt, Carmen Herrera, Mary Obering, Joseph Albers, Yves Klein, John McCracken, Carl André and Donald Judd. The movement was initially dominated by North American artists but spread to European painters where its format relaxed and hybridised with other artistic styles and technologies. In Britain painters like Peter Joseph, Tess Jaray and Bridgit Riley emerged followed by a younger generation of artist such as Covell and Brendan Lyons, who have pushed the limits and formats of physical painting off the canvas or formal support and into, minimal and/or illusory sculptural objects, conceptual environs and installation, allowing paint to become object, in line with but advancing minimalist ideals. Covell has established her place as a serious abstract paint-based artist at the beginning of the 21C, making real experiential objects, transforming and weaving the 2D into the 3D in a non-virtual world to create pieces of great beauty and complexity which at the same time demonstrating, clearly the perpetual yet paradoxical simplicity which under pins so much of the material world.

Covell from the ‘Flags’ series (Ukranian Colours)

Time, attitudes and the language around women’s and colonial art heritages have thankfully moved on and contemporary post minimalist abstraction is thriving. Early equivalent movements developed across Europe, not least influenced by Yves Klein whose work is directly referenced in Covell’s.

Yves Klein was part of the Nouveau realist movement a French artistic development which was at its peak between 1960 and 1970 and was founded by French art critic Pierre Restany and Klein (April 1960). Its aim was to find “new ways of perceiving the real”. Nine artists signed a manifesto declaration; Yves Klein, Martial Rayesse, Arman, Daniel Spoerri, Jean Tinguely, Jacques de la Villeglé, Raymond Hains, The Ultra-Lettrists and Restany himself. In 1961 more artists including Christo and Niki de Saint Phalle associated themselves with the group

Klein was also interested in the esoteric and spiritual, having read Max Heindal’s text, ‘The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception (1909), in 1949 in post-war France which was in turn influenced by French and German magical writers closely linked to organisations such as the Golden Dawn, Levi and the Theosophical society. Gurdjieff also spent time in France in the early 20C, but Klein joined an American Rosicrucian order, (he additionally undertook travelled to Japan prior to the formation of the Nouveau realist movement and became the first European to rise to the rank of Yodan (Judo master), his interest in the metaphysical was clear. A theme with resonates throughout Covell’s work and thinking.

Covell from the ‘Altered States’ installation

Klein painted monochromes as early as 1949, often intense monochromes linked to a specific place. He used primary and secondary colour monochromes but was disappointed by the public and critical response to the works and so focussed on a single primary colour from this point on, the famous ‘Yves Klein Blue’. Covell’s site specific installation ‘Altered States’ is in some part a homily to these pieces, exploring the same meditative and spiritual power of pure colour.

This spiritual element is constant, if not overt, in Covell’s work. Her Stations of the Cross series can be compared to Barnett Newman’s. (2)

Newman made 15 abstract works between 1958 and 1966 based on well-known Christian writings; Newman is also Jewish, as were many of the original minimalists; Stella and Albers were from Jewish refugee families and even Klein, once he began his esoteric path learned Hebrew to be able to understand some of the older Judaeo-Christian mysteries. Covell writes of her series;

““My polyptych painting ‘Stations of the Cross’ is intended to be a provocative work that deals with the spaces between life and death, the ethereal and the physical - where white meets black and light and dark symbolise the struggle of holding onto life whilst simultaneously letting go.

It is about the body as a container for emotions - fear, sadness, uncertainty, love, and of course hope....” (Covell 2022)

She has openly discussed her interest in theosophy and notions of the ‘sublime/divine’. Theosophy absorbed multiple religious teachings; comparing Jewish, Christian, Hindu and Tibetan Buddhist traditions, creating a new set of evolutionary histories for mankind.

Covell from the ‘Black and White’ series

Covell from the ‘Black and White’ series

One of the central tenets of Kabbalah, the Jewish esoteric (hidden) mystical teachings, which are central to most western esoteric and hermitic traditions, and which have been so often demonised as ‘Black Magic’ (thinly masking antisemitism), is that our universe springs from ‘No-thing’. Nothing has a particular spiritual meaning in many traditions.

Zev Ben Shimon Halevi writes, “…the Hebrew words AYIN, Nothingness, and EN SOF, the Endless, hover beyond the sphere of EN SOF AUR, the Light of the Limitless. This circle of Light, representing the Will of God, surrounds the Void of unmanifest Existence. The Holy One generated the Zim Zum, or contraction, that brought this first dimension into being. This set the stage for manifestation to begin.”(3) (Halevi, 2021). This belief that everything comes from nothing is the ultimate reductive abstraction and the Theosophists, like the Golden Dawn and Rudolph Steiner, and to some extent Jung (also coming from a central European cultural familiar with Rabbinic magic) developed systems of colour or colour theories which attributed complex meaning and power to specific colours.

Sartre wrote of ‘nothing’; “Is negation as the structure of the judicative proposition at the origin of nothingness? Or on the contrary, is nothingness, as the structure of the real, the origin and foundation of negation?” (Sartre 1993) (4)

Example of an early 20C esoteric colour meaning chart of the kind used by the Golden Dawn, SOL and the other magical orders and religious sects

The manifestation of the divine, through colour or ‘rays’ of colour was a theme with many of the 1960’s countercultural spiritual movements and each colour has its own set of values in the physical, psychological, spiritual and divine worlds. This sublime use of colour was sought by Klein and is another key to Covell’s work.

The prohibition of creating and worshipping images and idols in Judaism, Islam and indeed strict Lutheran sects, to which Kant belonged (before he too undertook a study of Hebrew) is transmitted down into abstraction and minimalism. As are the minimal and/or geometric forms of Hindu and Buddhist mandalas. The work at times seems to be trying to bridge the void between religious and scientific truths and realisations of the 20C.

This notion of the sublime is discussed at length by McHiggens in her essay ‘Can Abstract Painting be sublime’ and she uses Kant’s concepts to highlight the differences between the aesthetically beautiful and the sublime.

Covell from the ‘White Paint Sheets’ installation

Covell from the ‘Silver’ Series

The Sublime (5)

Sophie McHiggens writes, “the American abstract painters were concerned with the ‘sublime ‘– Newman’s ‘The Sublime is Now’ (6) greatly influenced the movement and its aims as well as its presentation to the public writing ; “The failure of European art to achieve the sublime is due to the blind desire to exist inside the reality of sensation (the objective world, whether distorted or pure) and to build an art within a frame of pure plasticity” (Newman 1948). There was some philosophical competition between North American and European cultural movements and manifestos during this period.

She continues: “Rosenblum’s 1961 ‘The Abstract Sublime’ (7) states “during the Romantic era, the sublimities of nature gave proof to the divine; today such supernatural experiences are conveyed through the medium of art alone. What used to be pantheism has now become a kind of “paint-theism”. The sacred nature of the contemporary art gallery as a form of religious space has been well discussed. Philosopher and writer Jeffery Kripal suggests that the two places where the divine is currently most present, in North American and European societies at least, are no longer the churches which were once sacred and supernatural but the galleries and hospitals, where the veils between the material and immaterial, living and dead are thinnest.

Mc Higgens highlights that whilst both Newman and Rosenblum both compare painterly abstraction to Kant’s notion of the formless, they avoid his second dynamical sublime entirely – hence the avoidance of natural and organic forms. She then exemplifies Rothkos’ ‘Seagram Murals’ (1957-59) emphasising that it is not just the work, but the space in which it is displayed, the lighting and the ritual around visiting them which elevates them to something even more sublime. Arguing further that with all artworks it is the light, in other words, the sight which is the critical factor (self-evident in many ways but often overlooked).

Citing that for Kant, “The first occurrence of the sublime is ‘mathematical’ the second is ‘dynamical’ (Kant 1790)” (8). He deems the mathematical an aesthetic experience (eg scale), whilst ‘Nature is dynamically sublime – not least because it inspires fear as much as pleasure’_ (Mc Higgens again.)

Covell from the ‘Zero’ series

On beauty, McHiggens supposes that; “Kant introduces us to the notion of the sublime via the transition from the beautiful; another significant faculty of judgement that is analysed in the… ‘Third Critique’. Whilst Kant’s initial reasoning suggests that the beautiful and the sublime share commonalities in that they ‘please in themselves’ (Kant 1790), namely that they yield pleasure over knowledge, the fundamental difference lies in their opposing boundaries. Whilst the beautiful is indexed to the form of an object, namely in that it presents definite boundaries, the sublime reigns in its total boundlessness.”

She argues that, “For Kant the sublime is akin to the formless; it is a sentiment with no fixed parameters”, it might be imagined to be like the sea or the sky.

However, “… The sense of overwhelming totality incites the imagination in a way that the beautiful fails to achieve. The pleasure yielded by experiencing the sublime, generates, for Kant a movement of the mind, rather than the restful contemplation as experienced by the beautiful”. This seems to be an idea underwriting many of the works of minimalist and abstract works of Covell. But it could also be argued that this is not solely the case and that other outcomes may arise from ‘beauty’; joy is created by beauty – and envy…and lust and sorrow. But the sublime returns us to the transcendent, timeless, boundless and is at once reductive and expansive. It allows one to step back from the personal into the transpersonal. The rejection of the organic/dynamic principles by abstract post-minimalist artists is perhaps something which needs to be further unpacked, as the human brain, filter for all this information, visual or lexical, and vehicle for consciousness and understanding the rules and systems of these philosophies, is organic. Without our bodies we experience nothing… which potentially takes back to the ‘Nothing’ of Halevi and Cordevero and equates directly to our (indivual( place in the (collective) ‘Divine’.

For Jung, Colour is an archetype, and it functions in this manner for many religious and spiritual organisations, but also for military coding and public life. People understand colour, it is almost universal that traffic lights follow a particular order, green for go, red for stop.

Scientists, philosophers, magicians and artists alike have developed colour theories to help define and control our understanding of the world/cosmos, Newton and Goethe are famous examples. Most religions have sophisticated colour-based theories and artists such as Joseph Albers also invested much energy in the ontology and theory of colour. (9) Albers previously associated with the Bauhaus movement published on colour theory in his treatise ‘Interaction of Colour’ in 1963.

Covell from the ‘Reds’ series

Number, shape and word are all considered sacred and Geometria is associated with magical practices, interculturally. There is much magic in a sacred circle or a cube of space. The Archetypes of colour continue to inspire even if knowledge of them is subconscious.

Klein’s Blue is traditionally the colour of Mary, the Magdalena or Tower in the Christian faith, echoing the earlier blues of (Hebrew) Binah the great mother, Mara; the sea and source of life, of Lilith, of dreams and sleep and the deep blue Egyptian star goddess Nuith. It is present in the illuminated manuscripts of the Christian monks and Kells as well as the paintings of Da Vinci. In Jewish traditions it is the colour of protection as well as of the mother. Covell is a mother herself and acknowledges both the inspiration of motherhood and its constraints as a self-reflective and formative process. Motherhood affects her space, her time to work and her physical and emotional sensibilities. Defining her as collective as well as individual. Parenting enforces a transpersonal stance and require that safe spaces are created. Covell extends this out into her worked objects. On walking into ‘Altered States’ all of these histories are present even if they not offered in a representational style. They contain all the complexities and simplicities and paradoxes of life.

The sacred and the profane.

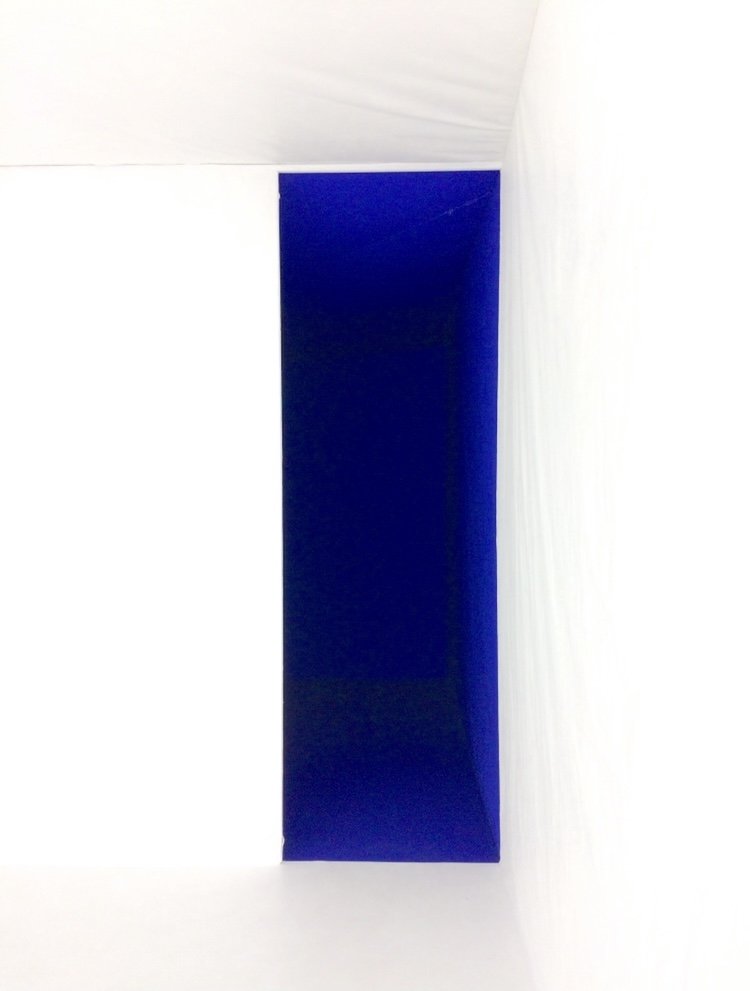

Covell ‘Blue’

Covell’s geometric works also nod to the formal requirement of minimalist abstraction, echoing McCracken’s free standing ‘planks’ such as ‘Portal’ from 1989 and go onto dialogue with works like Albers ‘Manhattan’ collage from 1963. Although very different in scale and without the formal, clean edge of a canvas or board support, Covell’s long collaged rectangles and triangles, in red, blue, yellow, black, and white, build up formal, repeated shapes in layers, to create unsupported substantial works with frayed boundaries, demonstrating the post-minimalist freedoms now permitted and enjoyed.

There is a dichotomy created by Covell’s ‘Silver series’ and ‘White paint sheets’ which transfigure the liquid paint into heavy, fabric seeming installations, hung from poles or pinned to the walls and then spread out into the space selected for their installation; in one ‘Silver’ is draped in a church, for the ‘White Paint Sheets’ an empty, white room, with soft white light. Sublime. They are static but depict weight, direction and an organic movement (even if frozen) the soft folds fall and avoid any tight or formal geometric shape, even though the original piece of paint from which they are sculpture is a square or a rectangle. Are they sheets or are they shrouds? This tension between material honesty and subverted form is a continual theme throughout her work, and the organic spills out in the fleshy ‘Reds’ and “Hearts’ series, the original geometry squished into luscious mucilaginous folds which start to remind the onlooker of clogged arteries and the very fleshy organ they feed and evacuated. The natural and organic are very much present and the works seem invigorated, corporeal and alive.

Covell ‘White Relief’

Lyons, Stephens and Covell have pushed the paint from flat surface into sculptural or relief forms – which both Kelly and Carl André did – creating subtle, eroded rectangular multi-edged panels, Stephen’s crisp and clean, the latter weathered, worked and compressed, deliberately failing to fit the mass of writhing, plastic paint into a classic frame or support.

All have a profound awareness of the traditions they emerge from and Covell’s work expresses, perfectly, the freedom, evolution and true form and colour use so central to abstract, post-minimalist painting in the 21C.

As Albers wrote ““In the end – the study of colour is the study of ourselves” and it may be no more possible to genuinely remove the ‘hand’ of the artist than the ‘hand’ of God, as both are ultimately metaphors for something far more experiential and far less tangible.

Sally ANNETT Novembre 2022

Links and References:

1. Henry.M. 2018 "Coenties Slip", P.127 Agnes Martin: Pioneer, Painter, Icon. Arizona: Schaffner Press.)

2. Kennicott. P 2017. Barnett Newman’s ‘Stations of the Cross’ draws pilgrims to the National Gallery. Washington Post. Available on line @ https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/barnett-newmans-stations-of-the-cross-draws-pilgrims-to-the-national-gallery/2017/04/13/e2cfc882-1ef0-11e7-ad74-3a742a6e93a7_story.html

3. Zev Ben Shimon Halevi. (2021). Kabbalistic Contemplations. Published by The Kabbalah Society.

4. Sartre. JP. (1993) Being and Nothingness. Simon and Schuster

5. McHiggens. S. (2015) Can Abstract painting be Sublime? Available on line at https://www.academia.edu/22297733/Can_abstract_painting_be_sublime

6. Newman.B & Strick.J. (1994). ‘The Sublime is Now’ Early work of Barnett Newman. Walker Art Gallery

7. Rosenblum. R. (1961) The Abstract Sublime. ART News. Feb Issue.

8. Kant’s ‘Analytic of the ‘Sublime’ (1790) is a 31 part essay in the second book of the ‘Critique of Judgement, which followed on from his The Critique of Pure Reason 1781 and the Critique of Practical Reason (1978)

Kant. I. (1790) Critique of Judgment. Translated from German by J.H. Bernard. 1951. New York, Hafner Press, London Collier Macmillan.

Kant. I. (2008) The Critique of Pure Reason. Penguin Classics.

9. Albers Joseph. A. (1963) The Interaction of Colour. Yale University press. Available on line @ https://interactionofcolor.com

For more information on Max Heindal follow : http://www.esotericquarterly.com/issues/EQ08/EQ0804/EQ080413-End.pdf